Live and Learn, Part 1: Sweet Potatoes in New England

It's not all that fun to write about failure. It's not all that fun to fail. But this weekend has been full of failures, mild annoyances, and terrible weather. Sigh.

Still, when you're done shaking your fist at the sky, you can learn from it. And if I share it, maybe you can learn from it too. Here's what we (reluctantly) learned about sweet potatoes this weekend.

Last year we had great success with growing sweet potatoes, and this season, despite the groundhog damage, we had a great big pile of them as well. They are so low-maintenance and so high-yield for us, we were starting to wonder why they are considered a Southern crop. I mean, we have no trouble growing them here in Massachusetts, so why aren't they considered a New England crop as well?

It's the curing, stupid.

Curing certain crops before storage helps them dry out and toughen up so they last longer in your root cellar. It's important to do it right, or your shelf life is cut waaaay back, as mold and rot take hold much more quickly if you haven't prepared them properly. Kinda like these:

Still, when you're done shaking your fist at the sky, you can learn from it. And if I share it, maybe you can learn from it too. Here's what we (reluctantly) learned about sweet potatoes this weekend.

Last year we had great success with growing sweet potatoes, and this season, despite the groundhog damage, we had a great big pile of them as well. They are so low-maintenance and so high-yield for us, we were starting to wonder why they are considered a Southern crop. I mean, we have no trouble growing them here in Massachusetts, so why aren't they considered a New England crop as well?

It's the curing, stupid.

Curing certain crops before storage helps them dry out and toughen up so they last longer in your root cellar. It's important to do it right, or your shelf life is cut waaaay back, as mold and rot take hold much more quickly if you haven't prepared them properly. Kinda like these:

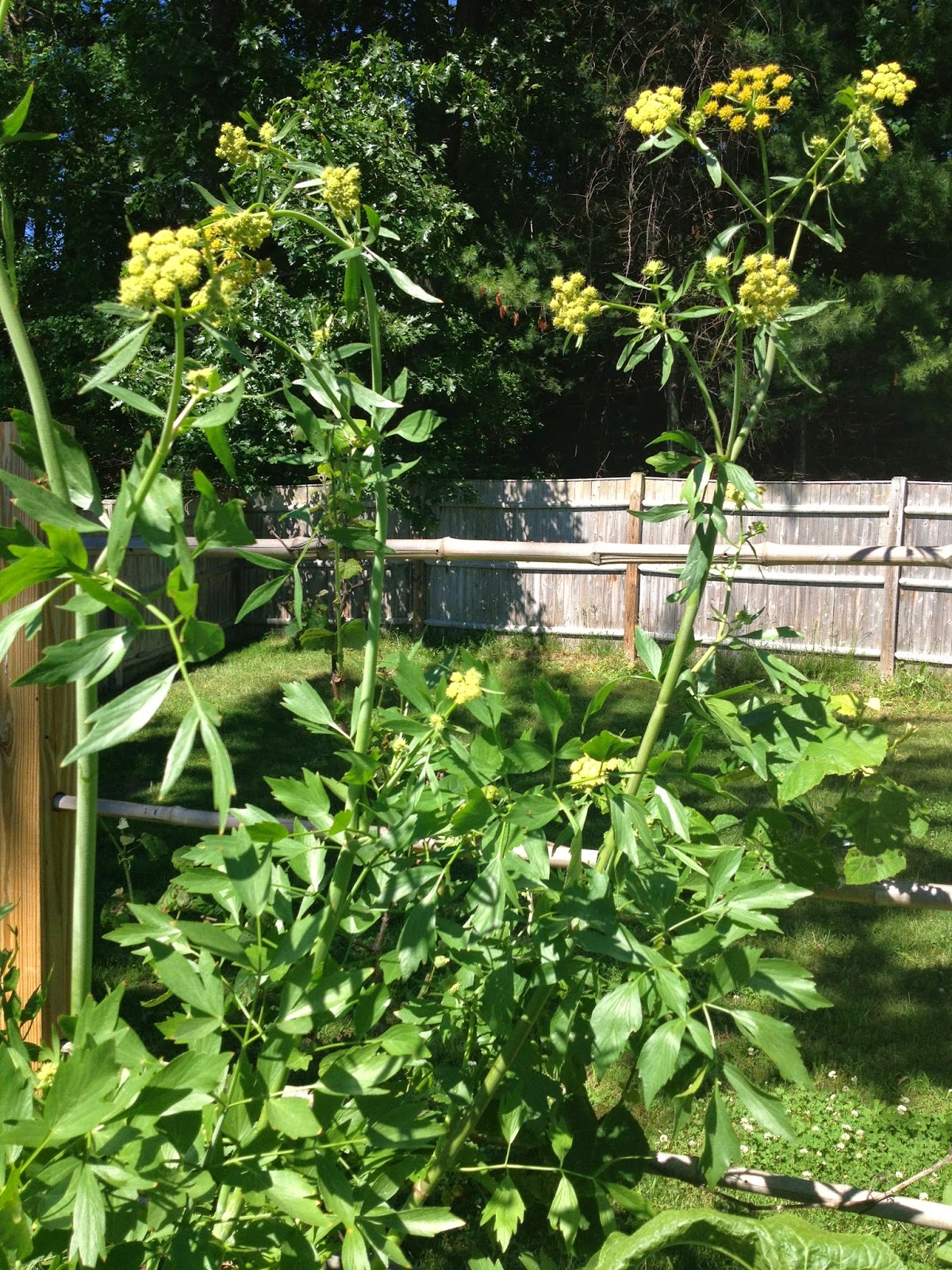

Kirk took his weekly look at our root cellar crops today, and discovered that half of our sweet potatoes were soft and moldy. That's them on the compost pile, which is all they're good for now.

So here's the thing about curing sweet potatoes. They need about two weeks in temperatures 80-90 degrees, with humidity at 80-90 percent, but with good air circulation.

We don't have anything close to those conditions naturally this far north by the time we're ready to harvest in October. So our attempt at curing this year involved keeping the dug-up sweet potatoes in the somewhat humid greenhouse tunnel for a day or two, then spreading them out to dry for another day (in temps around 40 degrees) before calling it good and putting them in crates in the basement.

Clearly, this is not how you do it.

If we were professional farmers, I suppose we could invest in some environmental controls, but for home use, we prefer a lower-tech (and lower carbon footprint) approach to our food. But if we can't cure these for long-term storage, the we need to re-think how exactly we'll use our sweet potatoes.

Next year, we will try three new things:

1. We'll try digging some up earlier. Maybe we’ll give a little check in September to see if they are up to size to be worth harvesting some. These we could probably cure in a cold frame more successfully, since we have warm sun in September, and we could keep high humidity in there by watering the ground. Ventilation would be trickier, but we could experiment with cracking the windows on the cold frame. If we could cure them well, the earlier harvest could perhaps be stored longer.

2. We'll eat them throughout the fall. We only had one dish with sweet potatoes so far this season, when we could have been eating them up instead. If we treat them more like a short-season treat, we can enjoy our harvest without trying to ration them into the winter, because that's probably not going to work.

3. We can plan ahead to store them by freezing them instead. That will probably mean a lot of mashed sweet potatoes throughout future winters (since they need to be boiled before freezing), but that's better than nothing.

After giving these ideas a try next season, we can decide if growing sweet potatoes is worth it, or if we should cut back the amount of space we give to them. Butternut squash lasts longer and tastes pretty much the same, so maybe that's a better use of our growing space in this climate.

Still, we're not ready to throw in the towel yet. We'll take this year's loss and try to learn from it to adjust for next season.

Which is about all you can do.

Comments

Post a Comment